Blog Credit : Trupti Thakur

Image Courtesy : Google

World’s Oldest Calender

Archaeologists at Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey have discovered what is thought to be the Earth’s oldest known Sun-and-Moon calendar, carved into a large stone pillar. This discovery, reported in a study on July 24, offers new insights into the development of early timekeeping methods.

Key Discovery

The pillar, estimated to be nearly 13,000 years old, is adorned with 365 V-shaped symbols, each likely representing a single day. This design reflects an advanced understanding of both solar and lunar cycles. The calendar includes 12 lunar months plus an additional 11 days, indicating that ancient societies had a sophisticated grasp of time.

Historical Implications

In addition to the calendar, the pillar features carvings of a bird-like figure, which may symbolize the summer solstice constellation. These carvings are believed to date back to around 10,850 B.C., a period marked by a major comet strike that possibly impacted the climate and culture of the region. This comet event is thought to have triggered an ice age, leading to changes in societal structures and potentially fostering new religious and agricultural practices.

Impact on Human Development

Martin Sweatman, one of the study’s authors, suggests that the comet strike and its environmental effects might have spurred the development of early writing systems. The findings at Göbekli Tepe not only demonstrate early human observations of celestial events but also enhance our understanding of prehistoric societies. This discovery sheds light on early astronomical practices and cultural dynamics in Turkey, revealing the complex knowledge systems of ancient peoples and paving the way for future advancements in human knowledge.

Facts About Göbekli Tepe

- Göbekli Tepe, in Turkey, is the oldest known temple complex, built around 9600 BCE.

- It has huge stone pillars set up in circles, which were likely used for ceremonies.

- Göbekli Tepe was built over 6,000 years before Stonehenge.

- It was likely constructed by people who didn’t farm, which is surprising because it was thought that farming came before building complex structures.

- What exactly Göbekli Tepe was used for is still debated, with ideas like ancestor worship being possible reasons.

- The site has detailed carvings of animals, showing early forms of symbolic thinking.

- Excavations started in the 1990s, revealing the importance of the site.

The history of calendars covers practices with ancient roots as people created and used various methods to keep track of days and larger divisions of time. Calendars commonly serve both cultural and practical purposes and are often connected to astronomy and agriculture.

Archeologists have reconstructed methods of timekeeping that go back to prehistoric times at least as old as the Neolithic. The natural units for timekeeping used by most historical societies are the day, the solar year and the lunation. Calendars are explicit schemes used for timekeeping. The first historically attested and formulized calendars date to the Bronze Age, dependent on the development of writing in the ancient Near East. In 2000 AD, Victoria, Australia, a Wurdi Youang stone arrangement could date back more than 11,000 years.[1] In 2013, archaeologists unearthed ancient evidence of a 10,000-year-old calendar system in Warren Field, Aberdeenshire.[2] This calendar is the next earliest, or “the first Scottish calendar”. The Sumerian calendar was the next earliest, followed by the Egyptian, Assyrian and Elamite calendars.

The Vikram Samvat has been used by Hindus and Sikhs. One of several regional Hindu calendars in use on the Indian subcontinent, it is based on twelve synodic lunar months and 365 solar days. The lunar year begins with the new moon of the month of Chaitra. This day, known as Chaitra Sukhladi, is a restricted (optional) holiday in India. A number of ancient and medieval inscriptions used the Vikram Samvat. Although it was purportedly named after the legendary king Vikramaditya Samvatsara (‘Samvat’ in short), ‘Samvat’ is a Sanskrit term for ‘year’. Emperor Vikramaditya of Ujjain started Vikram Samvat in 57 BC and it is believed that this calendar follows his victory over the Saka in 56 B.C.

A larger number of calendar systems of the ancient East appear in the Iron Age archaeological record, based on the Assyrian and Babylonian calendars. This includes the calendar of the Persian Empire, which in turn gave rise to the Zoroastrian calendar as well as the Hebrew calendar.

Calendars in antiquity were usually lunisolar, depending on the introduction of intercalary months to align the solar and the lunar years. This was mostly based on observation, but there may have been early attempts to model the pattern of intercalation algorithmically, as evidenced in the fragmentary 2nd-century Coligny calendar. Nevertheless, the Roman calendar contained very ancient remnants of a pre-Etruscan 10-month solar year.[3]

The Roman calendar was reformed by Julius Caesar in 45 BC. The Julian calendar was no longer dependent on the observation of the new moon but simply followed an algorithm of introducing a leap day every four years. This created a dissociation of the calendar month from the lunation.

Sub-Saharan African calendars can vary in days and weeks depending on the kingdom or tribe that created it.In the 11th century in Persia, a calendar reform led by Khayyam was announced in 1079, when the length of the year was measured as 365.24219858156 days.[4] Given that the length of the year is changing in the sixth decimal place over a person’s lifetime, this is outstandingly accurate. For comparison the length of the year at the end of the 19th century was 365.242196 days, while at the end of the 20th century it was 365.242190 days.

The Gregorian calendar was introduced as a refinement of the Julian calendar in 1582, and is today in worldwide use as the “de facto” calendar for secular purposes.

Etymology

The term calendars itself is taken from the calends, the term for the first day of the month in the Roman calendar, related to the verb calare “to call out”, referring to the calling or the announcement that the new moon was just seen. Latin calendarium meant “account book, register”, as accounts were settled and debts were collected on the calends of each month.

The Latin term was adopted in Old French as calendier and from there into Middle English as calender by the 13th century. The spelling calendar is from Early Modern English.

Equinox seen from the astronomical calendar of Pizzo Vento at Fondachelli-Fantina, Sicily

Prehistory

A number of prehistoric structures have been proposed as having had the purpose of timekeeping (typically keeping track of the course of the solar year). This includes many megalithic structures, and reconstructed arrangements going back far into the Neolithic period.

In Victoria, Australia, a Wurdi Youang stone arrangement could date back more than 11,000 years. This estimate is based on the inaccuracy of the calendar, which is consistent with how the Earth’s supposed orbit is thought to have changed during that time. The site is found near the world’s oldest known site of permanent aquaculture.

A mesolithic arrangement of twelve pits and an arc found in Warren Field, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, dated to roughly 8,000 BC, has been described as a lunar calendar and was dubbed the “world’s oldest known calendar” in 2013.

A ceramic artefact from Bulgaria, known as the Slatino furnace model, dated to roughly 5,000 BC, has been pronounced by local archaeologists and media to be the oldest known calendar representation, a claim not endorsed in mainstream views.

The Vučedol culture archeological findings in Vinkovci in modern-day Croatia included a ceramic vessel dated to 2,600 BC bearing inscribed ideograms of celestial objects, that was interpreted as an astral calendar, the oldest one in Europe that shows the year starting at the dusk of the first day of spring.

Vedic and Pre-Vedic Era /Ancient India

Timekeeping was important to Vedic rituals, and Jyotisha was the Vedic-era field of tracking and predicting the movements of astronomical bodies in order to keep time, in order to fix the day and time of these rituals, which were developed around the end of 2nd millennium BC as mentioned in “Sathapatha Brahmana”. This study was one of the six ancient Vedangas, or ancillary science connected with the Vedas – the scriptures of Hinduism, which was quoted by 5th-century BC scholar Yaska. The ancient extant text on Jyotisha is the Vedanga-Jyotisha, which exists in two editions, one linked to Rigveda and other to Yajurveda. The Rigveda version is variously attributed to sage Lagadha, and sometimes to sage Shuci. The Yajurveda version credits no particular sage, has survived into the modern era with a commentary of Somakara, and is the more studied version.]

The Jyotisha text Brahma-siddhanta, probably composed in the 5th century AD, discusses how to use the movement of planets, sun and moon to keep time and calendar. This text also lists trigonometry and mathematical formulae to support its theory of orbital, predict planetary positions and calculate relative mean positions of celestial nodes and apsides. The text is notable for presenting very large integers, such as 4.32 billion years as the lifetime of the current universe.

Water clock and sun dials are mentioned in many ancient Hindu texts such as the Arthashastra. The Jyotisha texts present mathematical formulae to predict the length of day time, sun rise and moon cycles.

The modern Hindu calendar, sometimes referred to as Panchanga, is a collective term for the various lunisolar calendars traditionally used in Hinduism. They adopt a similar underlying concept for timekeeping, but differ in their relative emphasis on the moon cycle or the sun cycle, the names of months and when they consider the New Year to start. The ancient Hindu calendar is similar in conceptual design to the Jewish calendar, but different from the Gregorian calendar. Unlike the Gregorian calendar which adds additional days to the lunar month to adjust for the mismatch between twelve lunar cycles (354 lunar days) and nearly 365 solar days, the Hindu calendar maintains the integrity of the lunar month, but inserts an extra full month according to complex rules, every few years, to ensure that the festivals and crop related rituals fall in the appropriate season.

The Hindu calendars have been in use in the Indian subcontinent since ancient times, and remain in use by the Hindus in India and Nepal, particularly to set Hindu festival dates. Early Buddhist and Jain communities of India adopted the ancient Hindu calendar, later Vikrami calendar and then local Buddhist calendars. Buddhist and Jain festivals continue to be scheduled according to a lunar system in the luni-solar calendar.

Roman Empire

The old Roman year had 304 days divided into 10 months, beginning with March. However the ancient historian Livy gave credit to the second early Roman king Numa Pompilius for devising a calendar of 12 months. The extra months Ianuarius and Februarius had been invented, supposedly by Numa Pompilius, as stop-gaps. Julius Caesar realized that the system had become inoperable, so he effected drastic changes in the year of his third consulship. The New Year in 709 AUC began on 1 January and ran over 365 days until 31 December. Further adjustments were made under Augustus, who introduced the concept of the “leap year” in 757 AUC (AD 4) The resultant Julian calendar remained in almost universal use in Europe until 1582, and in some countries until as late as the twentieth century.

Marcus Terentius Varro introduced the Ab urbe condita epoch, assuming a foundation of Rome in 753 BC. The system remained in use during the early Middle Ages until the widespread adoption of the Dionysian era in the Carolingian period.

In the Roman Empire, the AUC year could be used alongside the consular year, so that the consulship of Quintus Fufius Calenus and Publius Vatinius could be determined as 707 AUC (or 47 BC), the third consulship of Caius Julius Caesar, with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, as 708 AUC (or 46 BC), and the fourth consulship of Gaius Julius Caesar as 709 AUC (or 45 BC).

The seven-day week has a tradition reaching back to the ancient Near East, but the introduction of the “planetary week” which remains in modern use dates to the Roman Empire period (see also names of the days of the week).

Middle Ages

Christian Europe

Page of a 10th-century calendar from Einsiedeln Abbey (16 March to 9 April)The page for May in the Bedford Psalter and Hours ms. (British Library Add MS 42131, fol. 3r, early 15th century)

The oldest calendar of saints of the Church of Rome was compiled in the mid-4th century, under Pope Julius I or Pope Liberius. It contained both pagan and Christian festivals. The oldest extant manuscript of the early Christian calendar is the so-called Calendar of Filocalus, produced in AD 354. A more extensive martyrology was compiled by Jerome in the early 5th century. Jean Mabillon published a calendar of the church of Carthage made in ca. AD 483. The Anno Domini epoch is introduced in the 6th century. Extant calendars of the early medieval period are based on Jerome’s system of numbering of the years of the Metonic cycle, later called the Golden Numbers. A Carolingian-era calendar published by Luc d’Achery is entitled Incipit Ordo Solaris Anni cum Litteris a S. Hieronymo superpositis, ad explorandum Septimanae Diem, et Lunae Aetatem investigandam in unoquoque Die per xix Annos. (“here begins the order of the solar year with the letters placed by Saint Jerome, for the purpose of finding the day of the week and the age of the Moon for any day within [the cycle of] 19 years”). The Leiden Aratea, a Carolingian copy (dated 816) of an astronomical treatise of Germanicus, is an important source for the transmission of the ancient Christian calendar to the medieval period.

In the 8th century, the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede the Venerable used another Latin term, “ante uero incarnationis dominicae tempus” (“the time before the Lord’s true incarnation”, equivalent to the English “before Christ”), to identify years before the first year of this era. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, even Popes continued to date documents according to regnal years, and usage of AD only gradually became common in Europe from the 11th to the 14th centuries. In 1422, Portugal became the last Western European country to adopt the Anno Domini system.

The Icelandic calendar was introduced in the 10th century. While the ancient Germanic calendars were based on lunar months, the new Icelandic calendar introduced a purely solar reckoning, with a year having a fixed number of weeks (52 weeks or 364 days). This necessitated the introduction of “leap weeks” instead of the Julian leap days.

In 1267, the medieval scientist Roger Bacon stated the times of full moons as a number of hours, minutes, seconds, thirds, and fourths (horae, minuta, secunda, tertia, and quarta) after noon on specified calendar dates.] Although a third for 1⁄60 of a second remains in some languages, for example Arabic , the modern second is further divided decimally.

Rival calendar eras to Anno Domini remained in use in Christian Europe. In Spain, the “Era of the Caesars” was dated from Octavian’s conquest of Iberia in 39 BC. It was adopted by the Visigoths and remained in use in Catalonia until 1180, Castille until 1382 and Portugal until 1415.

For chronological purposes, the flaw of the Anno Domini system was that dates have to be reckoned backwards or forwards according as they are BC or AD. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, “in an ideally perfect system all events would be reckoned in one sequence. The difficulty was to find a starting point whence to reckon, for the beginnings of history in which this should naturally be placed are those of which chronologically we know least.” For both Christians and Jews, the prime historical date was the Year of Creation, or Annus Mundi. The Eastern Orthodox Church fixed the date of Creation at 5509 BC. This remained the basis of the ecclesiastical calendar in the Greek and Russian Orthodox world until modern times. The Coptic Church fixed on 5500 BC. Later, the Church of England, under Archbishop Ussher in 1650, would pick 4004 BC.

Blog By : Trupti Thakur

16

AugWorld’s Oldest Calender

Aug 16, 2024Recent Blog

AI HallucinationsMay 16, 2025

India’s Steps Into 6GMay 15, 2025

The New Accessibility Feature of AppleMay 14, 2025

The Digital Threat Report 2024May 13, 2025

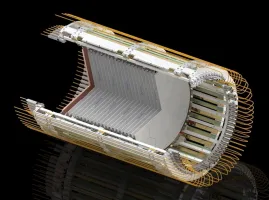

The MADMAX ExperimentMay 12, 2025